Jewelry Making: Past & Present now open

at The Museum for Islamic Art

Exhibition Dates: May 30, 2019 – November 16, 2019

About a year ago, I received an invitation for the revealing of hidden treasures in the warehouses of the Museum for Islamic Art. The jewelry of Islamic countries extends over a period of approximately 1300 years, from the beginning of the 7th century AD until the beginning of the 20th century. This art flourished and achieved remarkable achievements in a wide geographical area that stretched from India to North Africa, and yet it is very difficult to trace it since most of the treasures were melted to reusing the gold and silver with the changes of fashion history. We had the true pleasure of learning this magnificent history from Rachel Hasson, an expert on Islamic art.

The artists were invited to submit a jewelry proposal that would correspond with a piece of jewelry from the past. To choose one of the treasures and give it a contemporary interpolation. For me, this is the first time I have exhibited in a museum in Israel. And I am very excited about it as in my opinion, this museum is a true gem that not everyone knows about. its magnificent collection of ancient watches makes it a must-see point for visitors in Jerusalem.

The director of the Museum “Nadim Shiban” explained that the true goal of the “Museum of Islamic art” is to create a dialogue, a bridge of hope between people and the language of the jewelry that connects a thousand years of a dialogue between culture, religion, past, and present. The exhibition was curated by Dr. Iris Fishof through understanding and saying that jewelry is a universal language. As a cross-border art that has been used by all people throughout history.

The Koran does not prohibit the wearing of jewelry. In the Hadith (Collection of the Prophet’s Traditions), it is forbidden to wear gold jewelry, not for women, only for men. However, the work of Goldsmith itself was left mainly for Jews since it was considered a despicable undertaking in which the craftsman was liable to be dazzled by the great wealth and to take possession of the spoils. Therefore, on the one hand, due to the suspicious attitude of Muslims to Goldsmith, and on the other hand, the conveniences of dealing with goldsmiths, jewelers in Islamic countries, were usually Jews. And yet The Islamic art has left us with magnificent and aesthetically pleasing jewelry.

The first part of the exhibition will present works of Goldsmith attributed to the three monotheistic religions and intended for ritual or ceremonial purposes

For the second part of the exhibition deals with the contemporary silversmith, 45 Israeli artists and jewelers were expanding on the dialogue between past and present, each artist delved into the history of jewelry from concepts that deal with generation, tradition, and heritage to draw unique inspiration for their designs while giving new social and political contexts through art

For the second part of the exhibition deals with the contemporary silversmith, 45 Israeli artists and jewelers were expanding on the dialogue between past and present, each artist delved into the history of jewelry from concepts that deal with generation, tradition, and heritage to draw unique inspiration for their designs while giving new social and political contexts through art

These artworks touched my heart:

Vered Babai “touch wood” created beads inspired by the blue ceramic beads that she saw in the museum. From pencil sharpeners glued to each other like beads of luck that preserve the identity of the ancient beads in the structure and their geometric charm, but contrast them with color and materiality.

Artist Rill Greenfeld took a Moroccan fertility amulet dated from the 19th century and used it as inspiration for a contemporary fertility amulet which utilizes birth control pills in its design and purpose.

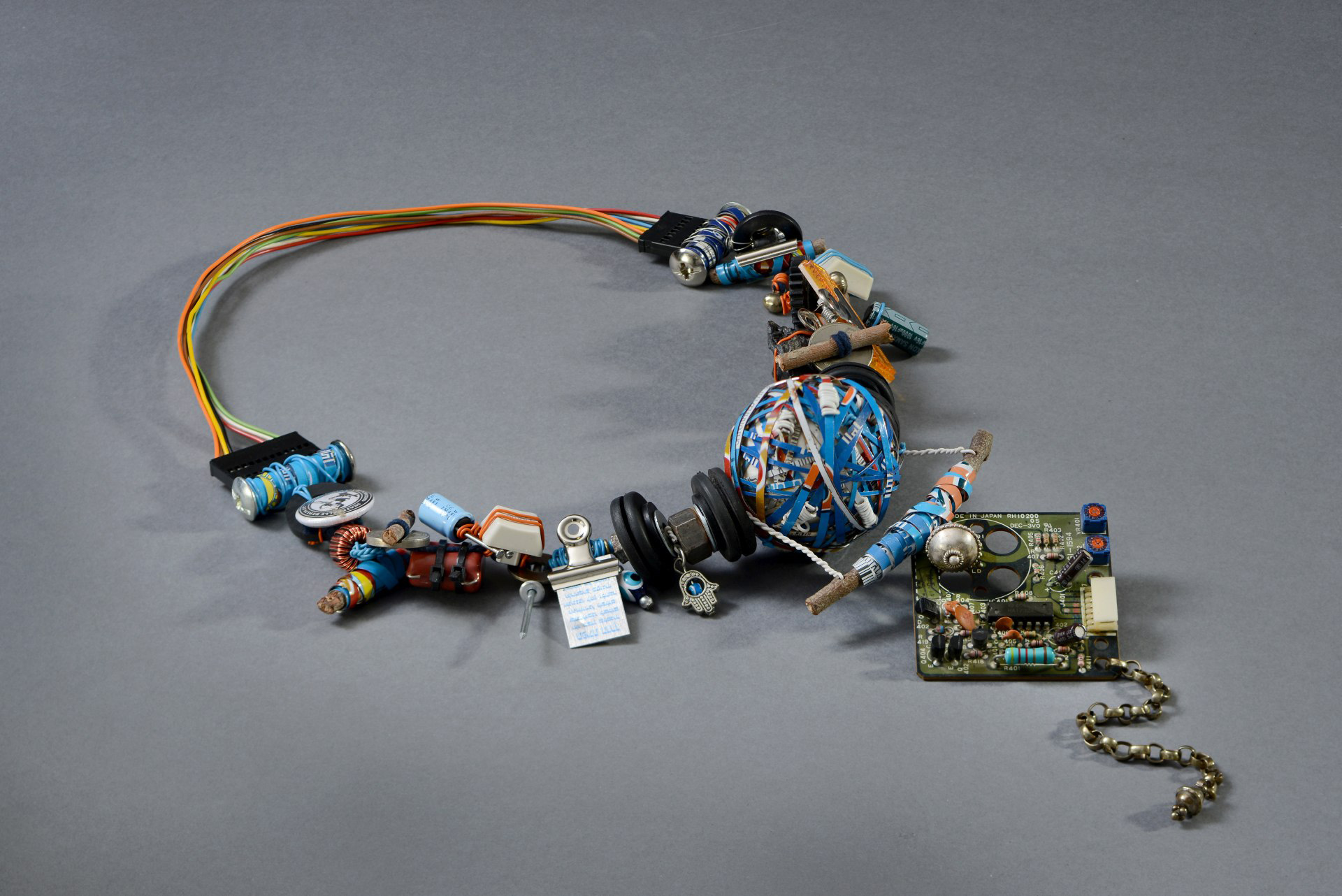

Artist Rill Greenfeld took a Moroccan fertility amulet dated from the 19th century and used it as inspiration for a contemporary fertility amulet which utilizes birth control pills in its design and purpose. Merav Rahat has created a jewel for the neck “What’s the Problem” as a local and personal contemporary interpretation of the visual language of the barbarian jewelry that tells of journeys, places and periods.

Merav Rahat has created a jewel for the neck “What’s the Problem” as a local and personal contemporary interpretation of the visual language of the barbarian jewelry that tells of journeys, places and periods.

My house ring was made in 3D print, and a sterling silver cast inspired by a ring from southern Morocco,

My house ring was made in 3D print, and a sterling silver cast inspired by a ring from southern Morocco,

designed to remind myself throughout the day where I come from and where I am going to and to ensure I can defend myself against anyone who blocks my safe journey home.

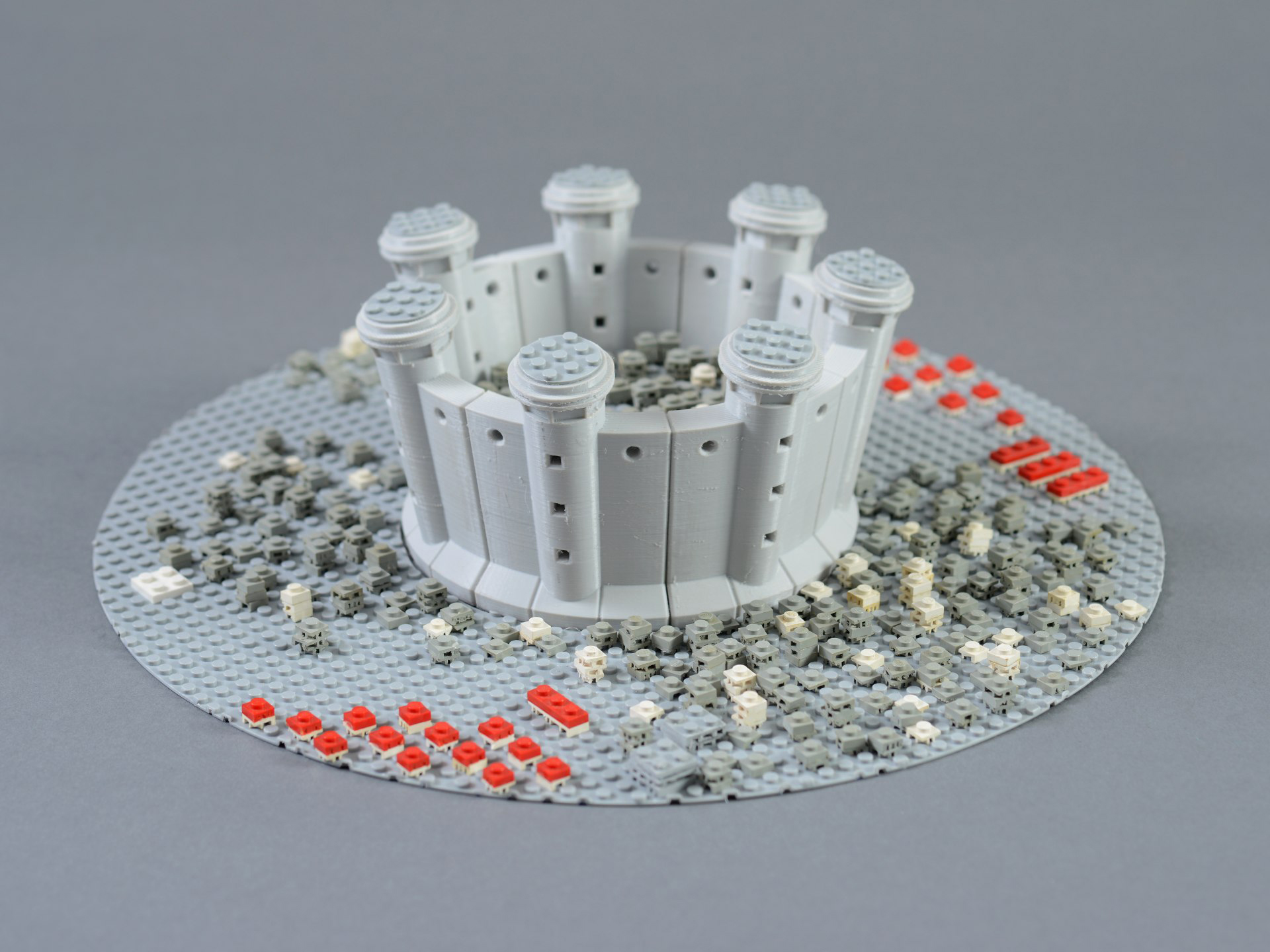

Ido Noy created an updated crown of Jerusalem walls inspired by the custom of women in the ancient Semitic world to put on their heads crowns designed as the walls of the city of Jerusalem of gold.

Ido Noy created an updated crown of Jerusalem walls inspired by the custom of women in the ancient Semitic world to put on their heads crowns designed as the walls of the city of Jerusalem of gold.

for moments it seems that every piece of jewelry needed to have its own personal display so that it could be viewed comfortably. However, in such a case, it is likely that the museum would need a number of floors. In fact, I found myself going back and forth to the same display cases to discover another detail that had disappeared before.

for moments it seems that every piece of jewelry needed to have its own personal display so that it could be viewed comfortably. However, in such a case, it is likely that the museum would need a number of floors. In fact, I found myself going back and forth to the same display cases to discover another detail that had disappeared before.

The lack of the display completes a detailed and precise catalog. The jewelry stories are presented as

The lack of the display completes a detailed and precise catalog. The jewelry stories are presented as

narrative passes through the picturesque past districts, and the close-up shots enable the close glance avoided in the jewelry cabinets.

Another part of the exhibition is a collection of ecclesiastical metalwork from the Franciscan Order which dates back from the 16th to the 19th century is exhibited for the first time to the public. These sacred metal objects have been accumulated throughout the centuries from the Mediterranean Christian nations, who regularly sent money and goods to assist the Franciscans charged with looking after the sanctuaries in the holy land.

A selection of Jewish vessels and amulets originating from the Levant are showcased from the private collection of William Gross. These pieces reflect the style and culture of their respective eras and regions, as well as the mutual language of folk art that served both Jews and Muslims. An exhibition spotlight will be focused on the works of Yemenite goldsmithing, a local profession for hundreds of years and on the jewelry of the late singer, Ofra Haza.

Curator: Dr. Iris Fishof

Artists: Anat Aboucaya Grozovski, Peter Bauhuis, Shiri Avda, Sean Axelrod, Vered Babai, Michal Bar, Shirly Bar-Amotz, Einav Benzano, Dania Chelminsky, Malka Cohavi, Israel Dahan , Dahan Taanach, Esther Knobel, Yael Friedman, Anat Golan, Noa Goren Amir , Rill Greenfeld, Dana Hakim Bercovich, Oded Halahmy, Naama Haneman, Noga Harel Rachel, Eden Herman Rosenblum, Vered Kaminski, Alona Katzir, Ariel Lavian, Hadas Levin, Noa Liran, Noa Nadir, Meirav Niv, Ido Noy, Tamar Paley, Shir Pins, Katia Rabey, Merav Rahat, Kobi Roth & Deganit Stern Schocken, Daniella Saraya, Inbar Shahak, Sara Shahak, Amit Shur, Gadeer Slayeh, Sari-Srulovitch, Noa Tamir, Rami Tareef, Yasmin Vinograd, Noa Zilberman.

photograph credit: Shai ben efraim, Inbar Shahak

This post is also available in: עברית (Hebrew)

1 Comment

Islamic art encompasses the visual arts produced from the 7th century onward by people who lived within the territory that was inhabited by or ruled by culturally Islamic populations. It is thus a very difficult art to define because it covers many lands and various peoples over some 1,400 years; it is not art specifically of a religion, or of a time, or of a place, or of a single medium like painting. The huge field of Islamic architecture is the subject of a separate article, leaving fields as varied as calligraphy, painting, glass, pottery, and textile arts such as carpets and embroidery.